The term 'Lost Films' has been coined so often by so-many different people over time that it has grown to lose all meaning. 'Lost Films' are now different things to different people and different today to 5, 10, 20... etc. years ago.

Frequently lists of 'Lost Films' are compiled, often with good intentions, but without a clear, predefined criteria for what constitutes a 'Lost Film'. Any understanding of the term is instead merely assumed, leading to confusion where opinions differ, and with more questions often created in place of answers.

It is necessary, therefore, to readdress this concept of 'Lost Films' and to come up with a new definition for the benefit of contemporary audiences – whether they are archivists, academics or members of the general public.

Coming up with a definition of 'Lost Films', however, is a complicated and difficult process. The following texts highlights some of the major questions, which were raised during the development of the 'Lost Films' project.

What is Film?

Before one can define a 'Lost Film', one must logically first define 'Film' itself. Does the term 'Film' refer solely to the material, which exists in our hands, or to the projected moving images, which exist in our minds... or to both?

If 'Film' is only a physical entity, then how should one consider those early television programmes that survive only as film copies? The media are different, yet the material is the same. Are they therefore 'Films' as well and if these film copies are also lost should they be considered 'Lost Films'?

On the other hand, if 'Film' is merely a performance, relevant to a particular place at a particular time, then can one say that all films are in fact 'Lost' since no two performances are ever wholly alike?

What is a film?

(1) Multiple Elements

Today one is faced with a number of possibilities from which to chose when trying to define a 'Film'. For example, there are original negatives; the elements which actually passed through the camera on the day of shooting. There are also correctly graded positive prints, which come closest to resembling what audiences see on screen. Is the 'Film' one of these or both (or something else besides)?

In the case of older films, meanwhile, there are also often preservation masters, which ensure the survival of the film's photographic content beyond the life of its initial carrier. Yet if a film is preserved from the only surviving original nitrate print, and that nitrate print then disappears, should it be considered a 'Lost Film'? Can one value a certain element over another because it comes from a point closer to the source?

Digital and other media pose an even more difficult question. If a film is not on film any more, can it still be considered 'Film'? Change the carrier and one can no longer technically call the element to which one refers a 'Film'. Thus, if a film was transferred to video in the past, and that video remains whilst no film copies are now known to survive, should it not be branded a 'Lost Film'?

What is a film?

(2) Multiple Versions

Mechanical reproduction is one problem, but what if the film's photographic contents differ between copies? F.W. Murnau's TARTUFFE (Germany, 1926), for example, is a film, which is widely available on DVD throughout the world and would thus never be considered a 'Lost Film'.

In line with common practice at the time, Murnau prepared several versions of the film for his various target markets, at home and abroad. A series of different negatives were produced for each territory using either footage obtained from a second camera or from alternate takes. As would be expected therefore, the versions differ slightly from one another.

No copy of the version released to German theatre goers as HERR TARTÜFF in 1926 has survived. Owing to the lack of materials available, those charged with restoring the film in 2002 opted to restore the American release version, TARTUFFE, and it is this version, which is available on DVD. Are multiple versions of one film to be considered merely separate parts of a single whole or can one justifiably claim that HERR TARTÜFF is a 'Lost Film' whilst TARTUFFE is not?

Temporarily Lost

Recent high profile discoveries such as BEYOND THE ROCKS (US, 1923, Sam Wood) in the Netherlands, or the longer copy of METROPOLIS (Germany, 1927, Fritz Lang) in Argentina have raised the public's awareness of 'Lost Films'.

Simultaneously, however, these discoveries have shown that many films, once thought lost forever, can later resurface in the collections of archives and private collectors. Far from 'Lost', therefore, they are instead merely 'misplaced'; temporarily abandoned to await rediscovery in future.

Should one therefore only label a film 'Lost' once all the archives and individuals have thoroughly searched their collections and recorded no surviving copies? Until this happens, meanwhile, is it not more appropriate to adopt alternative monikers, such as 'Presumed Lost'? Does this not, after all, carry a sense of uncertainty and imply the possibility that any of the films could resurface in future?

'Lost' or 'Never Was'?

'Presumed Lost' does not account for films, which were made but ultimately never released (and, in some cases, later destroyed) such as A WOMAN OF THE SEA (US, 1926, Josef von Sternberg). Likewise, neither does it account for those films that were started but never completed such as BEZHIN MEADOW (USSR) 1937, Sergei Eisenstein) or I, CLAUDIUS (UK, 1937, von Sternberg).

One could argue that the possibility of ever seeing these films in the way for which they were intended is also 'Lost' as a result of their never having been completed or released in the first place. Are these unfinished or unreleased films therefore 'Lost Films' too?

Authorship

Until the recent discovery in Argentina, METROPOLIS was for many years known only in contracted versions. Could METROPOLIS therefore have been considered another 'Lost Film', since the film widely seen over the years did not correspond to what the author had wanted his audiences to see?

Of course, what the author wants audiences to see isn't always a fixed thing. Charles Chaplin and René Clair both later modified their own work for re-release and it is these re-releases, which are more commonly available today.

In historiographical terms, meanwhile, the author's intention is somewhat irrelevant. A contracted version of a film, if shown to audiences in any part of the world at any time, constitutes an important historical document with as much validity as any version preferred by the author. Was METROPOLIS, therefore, ever really a 'Lost Film'?

Lost Picture vs. Lost Sound

Often in the case of films which included a separate soundtrack, as with the Vitaphone sound-on-disc process, the film elements have survived where the soundtracks have not. In others, the separate soundtrack elements have been the only elements to survive.

How does one measure picture against sound in these cases? Does picture outweigh sound in terms of importance because it is contained within the very fabric of the film material itself? Thus, could a surviving soundtrack without its picture element be considered a 'Lost Film' whilst a surviving picture element without its soundtrack not?

Alternatively, are picture and sound equal? Although different in nature to the film material, these separate soundtrack elements were an integral part of the film; existing in symbiosis with the photographic images on the strips of celluloid. If one part is lost then is the entire film not 'Lost' or, on the contrary, does the existence of the one component testify to the existence of the entire film?

Partially Lost

When it comes to incomplete films or 'fragments', it is difficult to ascertain an exact point from which they can be considered 'Lost'. Should a film be labelled 'Lost' only if more than half its original recorded footage is missing, for example? Alternatively, should a film be labelled 'Lost' only if the amount of missing footage significantly alters its original narrative and/or formal qualities?

While fragments of films such as Paul Wegener's first DER GOLEM (Germany, 1914, Henrik Galeen) and THE CASE OF LENA SMITH (US, 1929, Von Sternberg) have recently been unearthed, the films themselves could still be considered 'Lost'.

Alternatively, one could view that in absence of any other surviving material, these short fragments assume the responsibility once held by the complete films. They are the surviving relics, which bear all the traces of time upon the object. Can one still consider DER GOLEM and LENA SMITH 'Lost Films' if something of the film, no matter how little, has managed to survive, therefore?

'When the truth becomes legend...'

The term 'Lost Films' is often used to refer to films that survive intact but have disappeared from public view (or merely do not receive much attention). Ironically, films lacking any surviving physical trace, such as LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (US, 1927, Tod Browning), remain in the public consciousness precisely because of this lack. In this way, therefore, one would never consider them 'Lost Films'.

The implication seems to be that knowledge and memory of a film is just as, if not more, important than the film itself. One is therefore reminded of the conundrum of the tree falling in the woods with no one around to hear it: Does a film only exist if and when one knows about it?

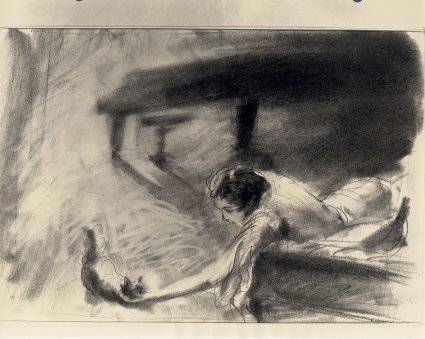

To maintain the existence of these 'Lost Films' (their life after death, as it were), it is , therefore, necessary that the continued knowledge and memory of these films be ensured. Providing access to related documents, which have managed to survive the years where copies of the film unfortunately have not, is one such way of doing this. It is for precisely this purpose that the 'Lost Films' website has been introduced.